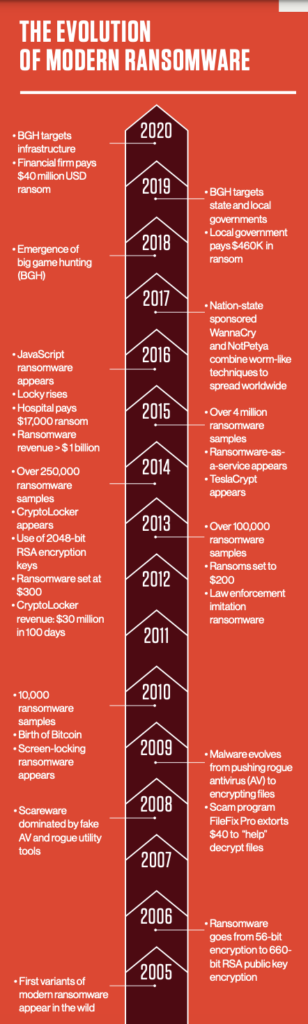

Following the evolution of ransomware, from a petty crime to a major economic windfall for global criminal enterprises, underscores why businesses should be deeply concerned about the threat. While its explosive growth over the past few years may make it seem otherwise, ransomware didn't come out of nowhere.

An Old Scheme

An Old Scheme

Even though ransomware has been in the headlines consistently over the past five years or so, the idea of taking user files or computers hostage by encrypting files, hindering system access or other methods - and then demanding a ransom to return them - is quite old.

In the late 1980s, criminals were already holding encrypted files hostage in exchange for cash sent via the postal service. One of the first ransomware attacks ever documented was the AIDS trojan (PC Cyborg Virus) that was released via floppy disk in 1989. Victims needed to send $189 to a P.O. box in Panama to restore access to their systems, even though it was a simple virus that utilized symmetric cryptography.

Monetization

Despite its long history, ransomware attacks were still not that widespread well into the 2000s - probably due to difficulties with payment collection. However, the emergence of cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin in 2010, changed all that. By providing an easy and untraceable method for receiving payment from victims, virtual currencies created the opportunity for ransomware to become a lucrative business.

eCrime - a broad category of malicious activity that includes all types of cybercrime attacks, including malware, banking trojans, ransomware, mineware (cryptojacking) and crimeware - seized the monetization opportunity that Bitcoin created. This resulted in a substantial proliferation of ransomware beginning in 2012. However, this ransomware business model is still imperfect, because while Bitcoin payments are easy transactions for cyber criminals to use, they are not always so easy for their non-tech-savvy targets to navigate. To ensure payment, some criminals have gone so far as to open call centers to provide technical support and help victims sign up for Bitcoin - but this takes time and costs money

As it started to gain more mainstream appeal, ransomware developers recognized it as just the method of monetary extraction they'd been seeking. Bitcoin exchanges provided adversaries the means of receiving instant payments while maintaining anonymity, all transacted outside the strictures of traditional financial institutions.

CryptoLocker Appears

The table was set perfectly for the entrance of CryptoLocker in 2013. This revolutionary new breed of ransomware not only harnessed the power of Bitcoin transactions, but combined it with more advanced forms of encryption. It used 2048-bit RSA key pairs generated from a command-andcontrol server and delivered to the victim to encrypt their files, making sure victims had no way out unless they paid a tidy sum of about $300 for the key.

The Gameover Zeus banking Trojan became a delivery mechanism for CryptoLocker. The threat actors behind the botnet were among the first to truly realize the potential value of ransomware with strong encryption, to extend their profits beyond traditional Automated Clearing House (ACH) and wire fraud attacks that target the customers of financial institutions. CryptoLocker's backers had hit pay dirt, kicking off ransomware's criminal Gold Rush.

CryptoLocker Gameover Zeus was shut down in an operation spearheaded by the FBI and technical assistance from CrowdStrike researchers. Even though it was out of operation within seven months of starting, it served as proof to the entire cybercrime community of ransomware's tremendous business upside. This was the true inflection point for ransomware's hockey-stick growth.

Within a few months, security researchers were finding copious numbers of CryptoLocker clones in the wild and criminals from all over the world were scrambling to get a piece of the action. Since then, many organized crime gangs have shifted investments and resources from older core businesses, including fake AV, into ransomware operations. The criminal technologists have been working overtime to serve these potential customers by cranking up specialized operations to develop better ransomware code and exploit kit components, flooding Dark Web marketplaces with their wares.

The Advent of Big Game Hunting

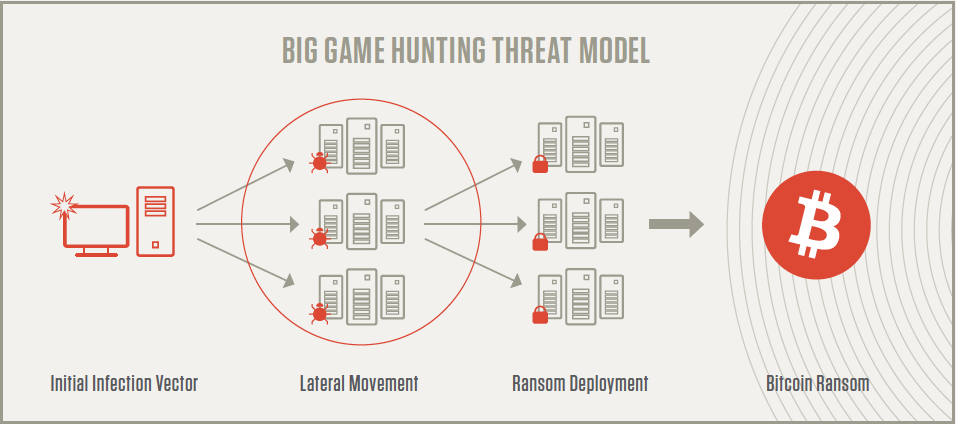

To optimize their efforts, ransomware operators decided to pivot from the "spray and pray" style of attacks that were dominating the ransomware space and focus on "big game hunting" (BGH). BGH combines ransomware with the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) common in targeted attacks aimed at larger organizations.

Rather than launching large numbers of ransomware attacks against small targets, the goal of BGH is to focus efforts on fewer victims that can yield a greater financial payoff - one that is worth the criminals' time and effort. This transition has been so pronounced that BGH was recognized as one of the most prominent trends affecting the eCrime ecosystem in the CrowdStrike® 2020 Global Threat Report.

In 2020, CrowdStrike Services observed the continued evolution and proliferation of eCrime adversaries engaging in big game hunting (BGH) ransomware techniques. This trend is continuing into 2021 - a recent high-profile example is the CARBON SPIDER/DarkSide attack on a U.S. fuel pipeline.